Embellishing the everyday

I’ve always been fascinated by human beings’ predilection for adding ornamentation to our surroundings. What is the impetus for decorating everything? A love of color, pattern, and decoration is obvious across India, and in Kachchh, where handicrafts have played an important role in culture and livelihoods for millennia, it’s especially hard to miss.

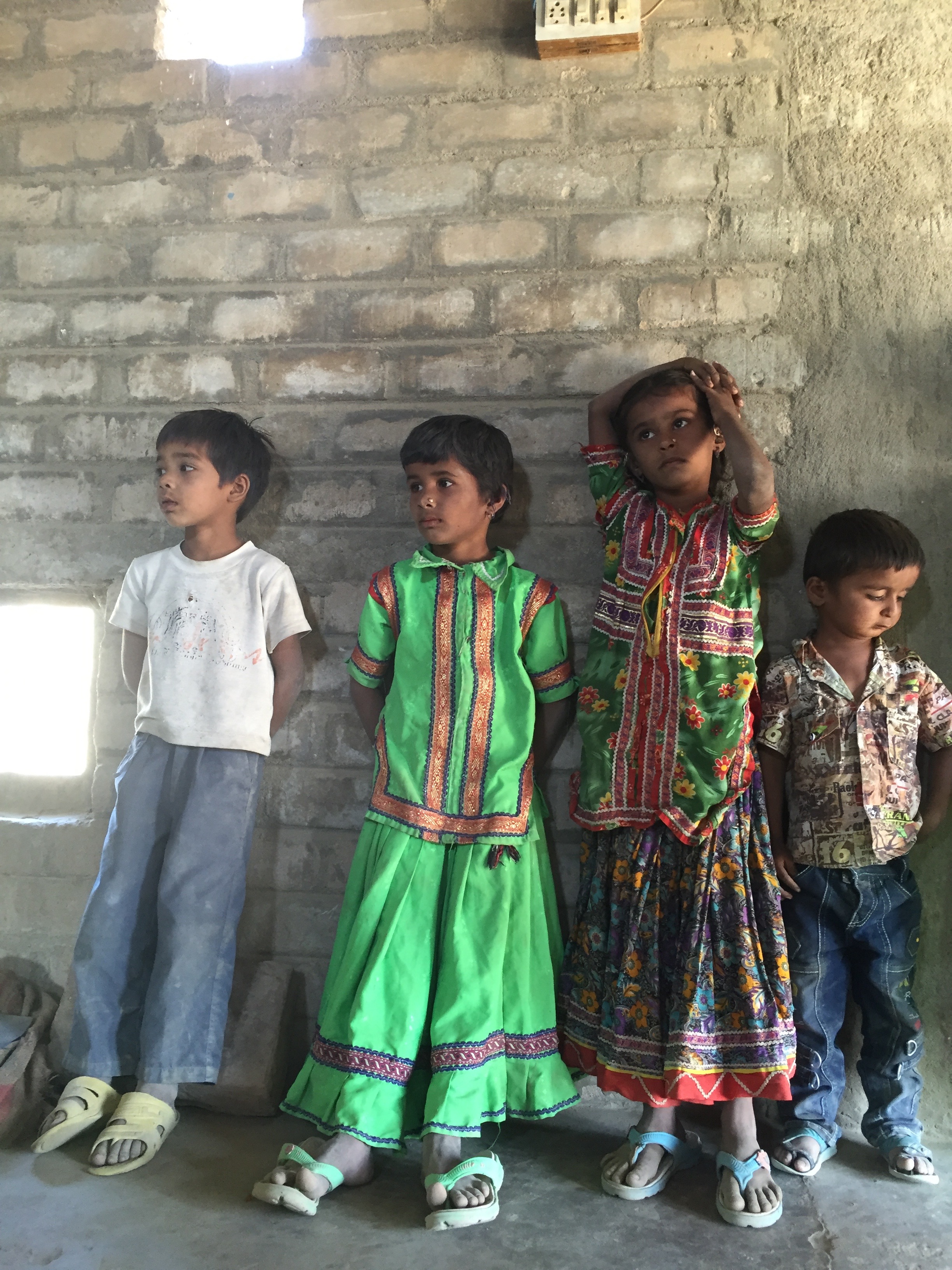

There’s personal adornment - intricately woven fabrics draped over the body, heavy silver jewelry encrusting arms and chest, beaded clothes for children. And among many rural communities, small dot pattern tattoos provide permanent embellishment. In the home there is neat mud work with glimmering mirrors embedded throughout, patterned pottery, embroidered bags. Of course, people everywhere like to dress up themselves, their children, and their homes.

But in India, adornment goes further. I wonder what it is about people here that draws them to go deck out things like trucks, taxis, cattle horns, camel straps? Author Pravina Shula suggests that “the Hindu concept of Darshan, of sacred sight…helps to shape India’s notable orientation to the visual.”

Applying surface decorations to everyday objects seems like it must stem from an innate desire to beautify. Beyond that, it is an opportunity to express cultural traditions and norms while also providing a space for individual creativity. Motifs are passed from one generation to the next, shifting slowly with along with personal preferences and new cultural influences.

Kachchh is a desert region of dun colored dust, white salt flats, and spiky acacia. For the pastoralist Rabari herders, the Ahir farmers, or the Meghwar communities in the desert and Banni grasslands, perhaps the lushly vibrant appliqué and embroidery work would seem to break the visual sparseness.

Typical landscape of Kachchh contrasted by bright textiles and decoration (see below)

In Traditional Indian Textiles, Gillow & Barnard write that ““By way of relief to the monotony of these dull tones, the people of the region have a deep-seated need for colour which is vented in the vibrancy of their clothes, animal trappings, and house decorations: the richness of the regions textile culture.” However, Judy Frater, a specialist in Kachchhi textiles who lived in the region for decades, writes that “Although colourful Rabari embroidery contrasts with relatively monochrome reality, it is not meant to counterbalance; the motifs traditionally used recognize and embellish important elements of everyday life.”

In this region, modes of transport, like oxcarts, and camel are just as valuable possessions, and are decorated almost as lovingly as clothes for an adored child.

Decorations are also a way to create and store wealth. For many communities, embroiderered textiles are considered a key piece of a marriage exchange, a way to build family ties and assess a woman’s skill. I’ve also learned that there are strong ties to auspiciousness in visual adornment. In Textiles & Dress of Gujarat, Eiluned Edwards writes that “auspiciousness is invoked in homes by ‘dressing’ them,” and that certain motifs are used on clothing, livestock, and in the home to signal prosperity and avert the malign. Mirrored glass, so common in embroidery and in Kachchhi mud work, might “deflect the evil eye which can be ‘overpowered by anything that dazzles and makes it blink.’”

I don’t know much about evil eyes. But I can certainly say that living here, I am frequently dazzled.

The White Rann of Kutch